How inclusive beauty is expanding its definition

One billion people worldwide have a disability, according to the World Bank, and yet only 4% of brands create products that cater for this population, according to P&G. In the beauty world, disability is often unconsidered. But now, a few early adopters are redesigning their products and packaging to appeal to an often ignored consumer group, reports The Future Laboratory.

Inclusivity has become a watchword in the beauty industry. The initial conversations about what it means to be an inclusive beauty brand were squarely focused on diversity, with Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty brand leading the movement. Launched in 2017 with 40 shades of foundation, which instantly sold out and in 2019 expanded to 50 shades, the brand answered a widespread consumer need for individuals who don’t normally see themselves in beauty products or advertising. Since then this mission of inclusivity has entered the mainstream, with drugstore brands like CoverGirl and Maybelline now also boasting 40 foundation shades and more diverse model casting.

The concept of inclusivity has also expanded, with several brands re-imagining their offerings and communications in order to bring more marginalised communities into the fold. The idea that make-up and skincare are solely of interest to women has come under scrutiny as gender-non-conforming ad campaigns and gender-neutral products celebrate a more broadly defined beauty consumer. But although the beauty industry is becoming more inclusive in terms of race and gender, it remains a realm exclusively created and designed for the able-bodied.

Most people with disabilities have to navigate a world that isn’t made for them. They face obstacles, both physical and metaphorical, on a daily basis. Beyond serious issues like lift accessibility or large print signs, even frivolous, fun things in life like fashion and beauty can be harder to enjoy. Almost half (49%) of disabled adults feel excluded from society (source: Scope), and according to a report by Think Designable, a collective that focuses on the benefits of inclusive brand practice, often these barriers are small, discreet exchanges that knock confidence and hinder participation. In the fashion world inclusive design has gained in popularity in recent years, with big names like designer Tommy Hilfiger and retailer Marks & Spencer launching disability-friendly, adaptive clothing.

But the beauty world has been slow to follow. Only a handful of beauty brands cater for disability, perhaps because of the belief that people with disabilities are not interested in their products. Blind YouTuber Molly Burke, who lost her sight when she was 14, addressed this misperception last year, stating: ‘People always ask me: ‘you can’t even see make-up, why do you like it so much?’ and I’m like, ‘going blind doesn’t change who you are, it changes how you live’.’ Another visually impaired influencer, blogger Emily Davison, has made a similar argument, that ‘disability isn’t a boundary to looking and feeling your best’.

Indeed, the disabled community are just as eager as the wider population for brands that cater for their interests. The global spending power of disabled people and their families has been calculated at £249bn a year, and not meeting their needs is estimated to cost UK businesses £420m a week (sources: Purple, Extra Costs Commission). ‘Like the rest of us, disabled people want to spend their money on the products they want, the services they need and the brands they love,’ says Marianne Waite, founder and director of Think Designable. There are many routes for beauty brands looking to make themselves more inclusive, from making products more readable for the visually impaired to adapting product design for different hand grips.

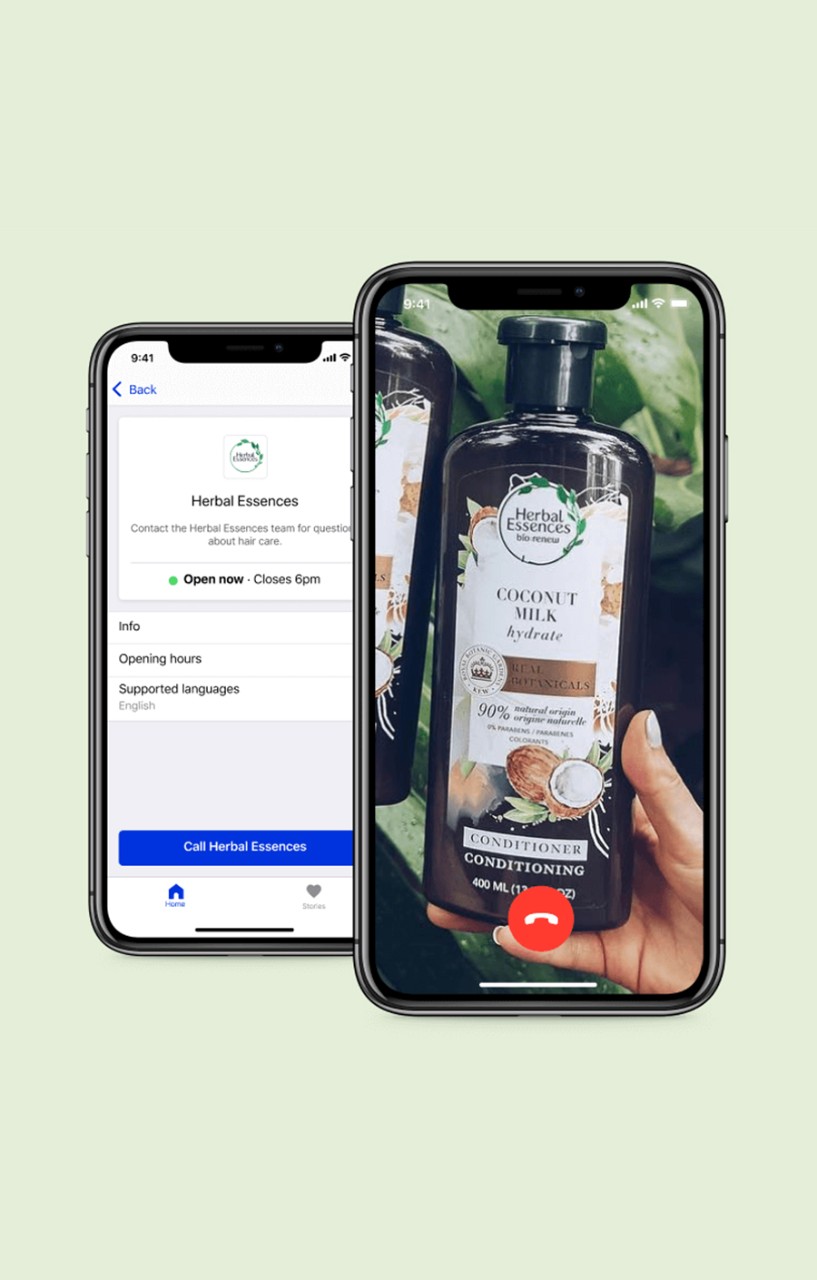

A leader in the industry has been French skincare brand L’Occitane, which has put braille on some of its packaging since 1997 and now includes the lettering on 70% of its products. P&G-owned Herbal Essences made headlines in 2018 for the launch of a new bottle design for its Bio: Renew range with tactile printing on the back. Instead of using braille, which some visually impaired people can’t read, the brand uses a simple system of circles and lines to differentiate between shampoo and conditioner. The latter has two rows of raised circles on the back while the former has four raised straight lines. ‘This can and will become standard for the beauty industry,’ Sam Latif, who led the new bottle design, told Vogue Business. In October 2019, the brand announced that not only would the tactile design expand to all its shampoo and conditioner lines in January 2020, but that it is launching an Amazon Alexa skill with the Be My Eyes app to answer blind and low-vision consumers’ haircare questions.

Using technology as a mediator between product and consumers is even more important for the disabled community. Japanese skincare brand Shiseido demonstrated this when it teamed up with Google on the Braille Nails project. Describe as a vision experiment, Braille Nails combined the growing popularity for press-on fake nails with the need to solve real-life problems for the blind. The nails act as sensors that link to a small Cloud vision camera, which can be worn as a badge. When the wearer makes a particular hand gesture the camera reads the environment around the nail and describes it back to the wearer. Gestures such as pointing to the sky for a weather report or giving a thumbs-up to describe the environment ahead helps users to understand ‘the world beyond the reach of their cane’.

Beyond making products more accessible to the visually impaired, the next step in inclusive beauty will be reconsidering the product design itself through the lens of dexterity. In March 2019 actress Selma Blair, who suffers from multiple sclerosis, posted a tongue-in-cheek video on Instagram of a make-up tutorial that highlights the issue. ‘Here is my solution to applying make-up with a lack of fine motor skills,’ she wrote in the caption. ‘#laugh and feel free to reapply my makeup.’

Also in March, start-up Grace Beauty announced three concepts for different grips for a mascara wand for those with limited dexterity. The first, the Safe Grip, attaches to the top of the mascara to offer a wider surface area and ensure better control; the Square Grip has been designed for both the lid and the base of the mascara to create more texture and again ensure better grip. The Ring Grip, meanwhile, has been created as a general aid for everyone, allowing users to have a much looser grip on a mascara tube without having to worry about dropping it.

While it is not clear whether these concepts will ever be turned into reality, another brand, Kohl Kreatives, has already launched its own disability-friendly make-up brushes. The Flex Collection brushes are designed to stand up on their own, making them easier to pick up, and each of the brushes has a flexible head, which means they can be positioned at different angles for greater control. Founder Trishna Daswaney told Vogue that making beauty products accessible means anyone, no matter their abled-ness, can use them. ‘It was about creating products that non-disabled people can use, as well as someone with Dupuytrens, MS, Parkinson’s. To me that’s what inclusivity is, truly something for everyone.’